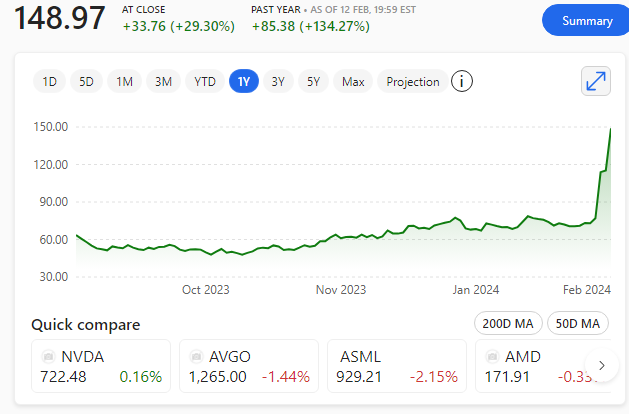

The rapid acceleration of artificial intelligence has created an unexpected bottleneck that few outside the semiconductor world saw coming.

A potential shortage of the high‑bandwidth memory (HBM) that modern AI systems depend upon has become a real issue.

As models grow larger and more capable, their appetite for memory grows even faster. The result is a looming constraint that could shape the pace, cost, and direction of AI development over the next five to ten years.

The issue

At the centre of the issue is the simple fact that AI models are no longer limited by compute alone. Training and running advanced systems require vast quantities of specialised memory capable of moving data at extraordinary speeds.

Only a handful of manufacturers produce HBM, and scaling production is slow, expensive, and technically demanding.

Even with aggressive investment, supply cannot instantly match the explosive demand driven by AI labs, cloud providers, and data centres.

The growing number of companies building on these models is only adding to the concerns.

If shortages intensify, the effects could ripple widely. Training costs may rise as competition for memory pushes prices higher.

Smaller companies could find themselves priced out of cutting‑edge development, deepening the divide between the largest AI players and everyone else. Hardware roadmaps might slow, forcing engineers to prioritise efficiency over sheer scale.

AI deceleration?

In the most constrained scenarios, progress in frontier AI could decelerate simply because the physical components required to build it are unavailable.

Is this crisis inevitable? Not necessarily. The semiconductor industry has a long history of overcoming supply constraints through innovation, investment, and new fabrication techniques.

Alternative memory architectures, improved model‑compression methods, and more efficient training strategies are already being explored.

Yet the demand curve remains steep, and the next few years will test whether supply chains can keep pace with AI’s ambitions.

A genuine memory crunch is not guaranteed, but it is plausible enough that the industry is treating it seriously.

If nothing else, it highlights a truth often forgotten in the excitement created around new technological developments, in this case… AI.

Even the most advanced intelligence still relies on very real, very finite physical infrastructure.